Archaeologists have unveiled the most detailed map ever produced of the earth beneath Stonehenge and its surrounds.

They combined different instruments to scan the area to a depth of three metres, with unprecedented resolution. Early results suggest that the iconic monument did not stand alone, but was accompanied by 17 neighbouring shrines.

Future, detailed analysis of this vast collection of data will produce a brand new account of how Stonehenge’s landscape evolved over time.

Among the surprises yielded by the research are traces of up to 60 huge stones or pillars which formed part of the 1.5km-wide “super henge” previously identified at nearby Durrington Walls.

“For the past four years we have been looking at this amazing monument to try and see what was around it,” Prof Vincent Gaffney, from the University of Birmingham, said at the British Science Festival.

The research is also described in BBC Two documentary to be screened on Thursday.

“What was within its landscape?”

Most of the land surrounding Stonehenge had not been surveyed in this manner before and Prof Gaffney, the project’s lead researcher, said one key question always remained: “Was it really an excluded place, where only special people would come?”

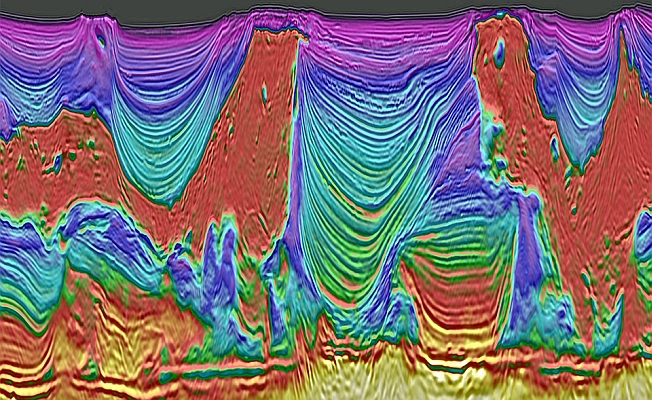

The team’s new three-dimensional map, which covers an area of 12 sq km or 1,250 football fields, shows that this was not the case.

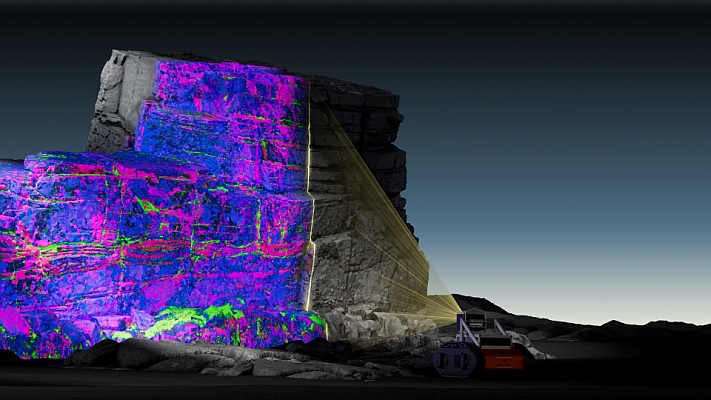

Researchers used six different techniques to scan the whole site at different depths below the surface.

Amongst their instruments was a magnetometer, a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and a 3D laser scanner.

Nishad Karim, a researcher at the University of Leicester, has used similar instrumentation to reconstruct 16th century Tudor tombs.

She told the BBC: “Using GPR and other techniques, these researchers have been able to virtually see through the ground and explore what civilization looked like thousands of years ago.”

Under one of the numerous mounds, they identified a 33m-long timber building about 6,000 years old, probably used for ritual burials and related practices, possibly including excarnation (stripping flesh from bones).

“[The building] has three rows of roof-bearing posts. It is around 300 square metres and slightly trapezoidal, which is interesting because in the same period on the continent, about 100 to 200 years earlier, we also find this type of trapezoidal building related to megaliths [giant stones],” said Prof Wolfgang Neubauer, director of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute, which was also involved in the research.

Another 17 mounds revealed previously unseen ritual monuments about the same age as Stonehenge itself.

The dating was done based on their shape. “We know what some of these things look like, so we can classify them,” Prof Gaffney explained.

A first inspection of the Cursus and the Durrington Walls, located north and north-east of Stonehenge, also revealed new insights.

The work unveiled two additional pits inside the prehistoric Cursus, an enormous, elongated circular trench originally named because it reminded its discoverers of a Roman racing track.

The Cursus is aligned in the East-West direction, and the pits were found one in each end, pointing to Dusk and Dawn.

This particular alignment is closely related to the position and orientation of Stonehenge, which was built as we know it some 300 to 500 years later.

The large separation in time indicates that both monuments were not conceived or planned as a whole. “The structures guide the builders. Once you have some things in place, other things happen because those already exist,” explained Prof Gaffney.

He and his team also found evidence of huge stones or timber posts lying three metres below the mounds that form the Durrington Walls.

“[These solid blocks] completely redefine the development of the Durrington Walls,” he told the BBC.

All of these preliminary findings reflect the complexity of the landscape’s history and evolution, which will be slowly uncovered once the researchers start the in-depth analysis of the data.

That analysis will reveal more precisely how the site evolved through the ages.

“We are starting to see the growth of fields encroaching on it. That’s important because it tells us about changing relationships to Stonehenge,” Prof Gaffney said.

“Eventually, we start to see the living returning, bringing agriculture. It becomes more the archaeology of the mundane, rather than the arcane.”

Dr Nick Snashall, National Trust Archaeologist for the Avebury and Stonehenge World Heritage Site, said: “Using 21st-century techniques, the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes team has transformed our knowledge of this ancient, precious and very special landscape.

“Their work has revealed a clutch of previously unsuspected sites and monuments showing how much of the story of this world-famous archaeological treasure house remains to be told.”

Source: BBC